Health is a Human Right: Achieving Health Equity NIWRC’s Participation in CDC Museum Exhibition

From November 25, 2024 - August 1, 2025, the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, presents “Health is a Human Right: Achieving Health Equity.” This exhibition looks at how communities across the U.S. are working toward solutions to offer opportunities for all Americans to thrive in the 21st century. Through a compelling installation in the CDC Museum’s 5,000-square-foot gallery, visitors may engage with photographs, documents, media, artwork, and objects.

Representative of the entire country, the organizations, governments, and initiatives profiled are diverse in their mission and focus. They collectively reflect how communities embrace public health practices so that every person may thrive. Focused on “good news wins,” the exhibition details stories of communities that advance health equity in housing, education, and healthcare delivery. For example, it discusses the role of faith leaders in preventing HIV or tobacco use, looks at efforts to address food equity, and examines the community school movement.

But good news only goes so far: Some stories call out systemic crises. For example, the exhibition talks about the maternal health disparities among communities of color, particularly among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women, by discussing the historical conditions that contributed to such alarming current conditions and the grassroots and government activists working to address the situation.

One important story centers on grassroots organizations and governments that are working to address violence in Indigenous communities, particularly the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People (MMIWP) crisis. Opening with an acknowledgment of the AI/AN risk factors for historical violence, including multilayered traumas resulting from war and loss of land, language, access to traditional ways, and cultural identity, it provides data about how Native communities continue to face the highest rates in the U.S. of assault, abduction, and murder, particularly among women. Profiled efforts by the U.S. government include Operation Lady Justice (OLJ) and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs).

Hearing from Indigenous voices is critical; the exhibit organizers worked with the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center (NIWRC). The exhibit includes many of NIWRC’s collateral materials and publications, underscoring the protective factors of tradition and culture.

Without a doubt, the highlight of the display and the entire exhibition is an empty chair draped with a red shawl created by Connie Black Bear-Brushbreaker Ga Wiyan Sni Win (Woman Who Doesn’t Look Back, Sicangu Lakota). Representative of Indigenous activism, the chair and shawl symbolize a missing, murdered, or victimized loved one. Similar chairs appear at hearings held by the Not Invisible Act Commission (NIAC) and other hearings where people testify.

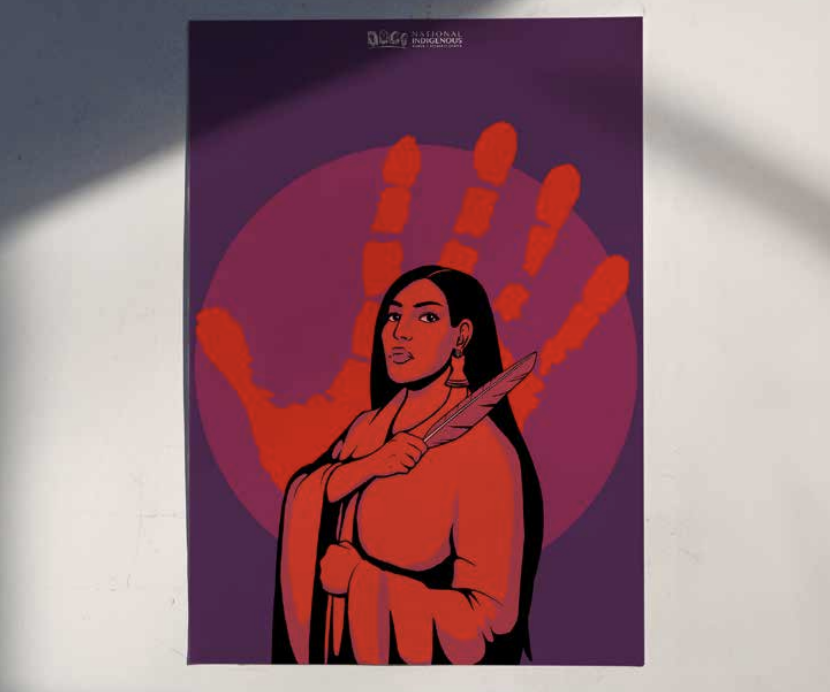

For her dramatic shawl, Connie drew upon the poster, also included in the exhibit, “No More Stolen Sisters,” created by brother and sister duo Nick Alan Foote and Kelsey Mata Foote (Tlingit, Taakw.aaneidí). The artists, originally from Southeast Alaska, want to amplify the dire need to address the systemic barriers that allow this horrific reality to persist and to amplify the voices of advocates and families working tirelessly to share their stories, demanding justice and restoring safety.

The artwork portrays a Native woman adorned in her robe regalia, holding a feather across her chest with resolute countenance and stance, conveying a message all advocates share: Enough is enough. It is an intentional reflection on MMIWP and what has persisted for generations, employing red, violet, and purple colors to symbolize the spectrum of violence by Native women and children across Tribal Nations and Native Hawaiian communities. It stands in solidarity with daughters, sisters, mothers, and aunties who were taken from their nations and communities. Kelsey’s and Nick’s children’s books, the first of their kind written in Tlingit, will also be featured in another section of the exhibition that discusses language revitalization initiatives undertaken by Native communities.

The MMIP exhibit will bring attention to a crisis few Americans know about. With knowledge comes power. The CDC Museum expects more than 100,000 people, including school groups and public health professionals worldwide, to visit the exhibition in Atlanta. An online version will further amplify this story and will be available at www.cdcmuseum.org.

In addition to the NIWRC and divisions and programs across the CDC, contributors to the overall exhibition include, among others, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, the City of Newark, New Jersey, the Rhode Island Department of Public Health, the Center for Black Health Equity, the California Nails Salon Collaborative, Black Mamas Matter, and the Healthy Neighborhoods program City of San Antonio’s Metropolitan Health District.