Supreme Court Update, June 2024 by STTARS

Grants Pass v. Johnson

“What is clear is the following: Grants Pass, as a community, tried to ensure the removal of its unhoused relatives”

The STTARS Indigenous Safe Housing Center’s vision (STTARS) is safe housing for ALL our relatives. This includes relatives who experience multiple systems interactions, including and especially with the criminal justice system and various child welfare systems. STTARS was established to address the intersection of housing insecurity/experience of homelessness and gender-based violence for American Indians, Alaska Natives (AI/AN), and Native Hawaiians (NH).

As a part of the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center (NIWRC), we utilize a Tribal sovereignty framework as a prevention-bolstering response within our Tribal Nations. However, unhoused relatives exist in both on and off-reservation communities. What follows in this article is an overview of a pending US Supreme Court Case that touches on the unhoused crisis in urban areas, Grants Pass v. Johnson (No. 20-35752 (9th Cir. 2023)), in which cert was granted after a 9th Circuit decision.

Due to the monumental nature of this case and the interests of STTARS and supporting organizations, the StrongHearts Native Helpline filed an amicus brief as the lead organization. STTARS was instrumental in the coordination and completion of this brief, and STTARS, NIWRC, the Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center (AKNWRC), and the Alliance of Tribal Coalitions to End Violence (ATCEV) were all supporting sign-on organizations. To read a copy of our brief, please visit here: bit.ly/4dGGXVD. STTARS worked with the National Homelessness Law Center, which secured a pro bono firm for StrongHearts’ brief. With two members of STTARS on StrongHearts’ Board of Directors, the partnership on this endeavor was easily met. STTARS’ material and input were heavily utilized for the brief, as was incredibly relevant data from the StrongHearts Native Helpline.

In Grants Pass v. Johnson, the 9th Circuit held that punishing unhoused individuals for public camping would violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment if the unhoused did not have access to shelter elsewhere. The Court reasoned that the conduct the government was punishing through the ordinances that the city of Grants Pass put into place was simply an unavoidable consequence of being unhoused. This is the first SCOTUS case to address unhoused relatives since the 1980s.

Oral arguments in this case were held April 22, 2024.

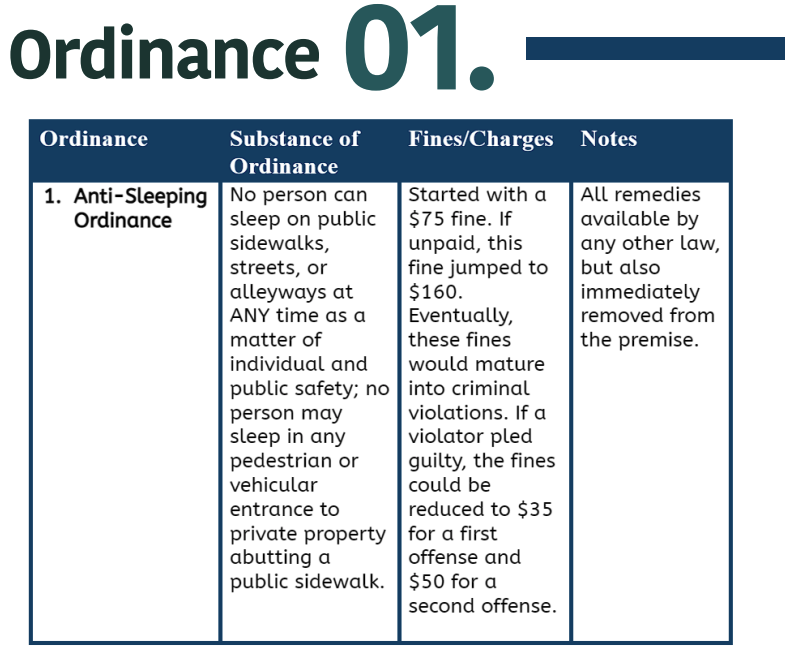

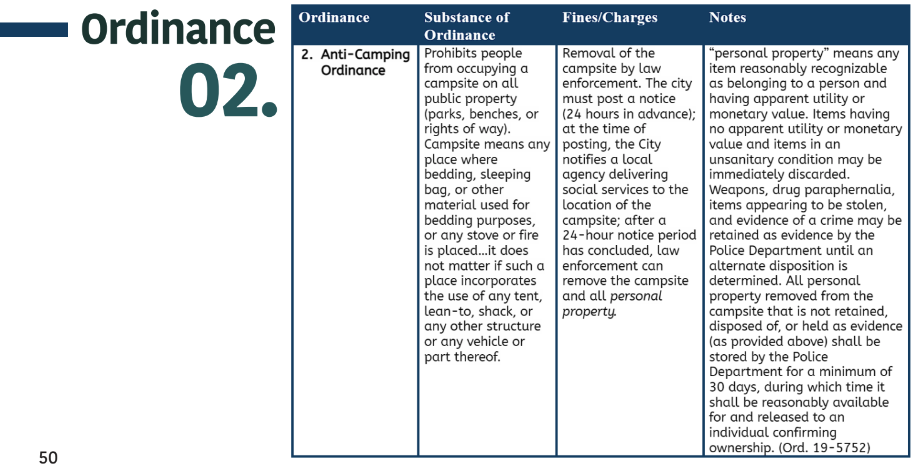

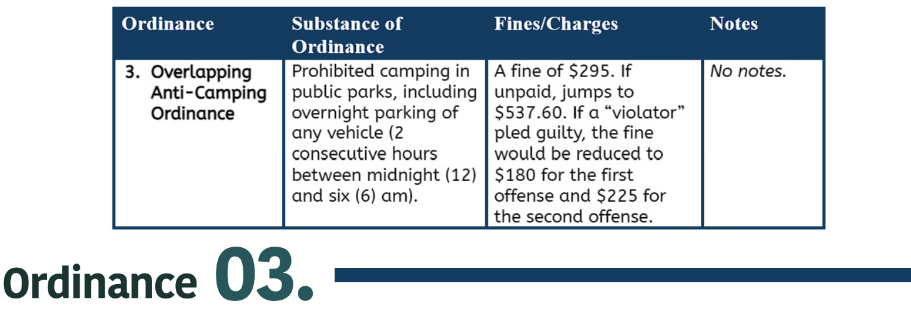

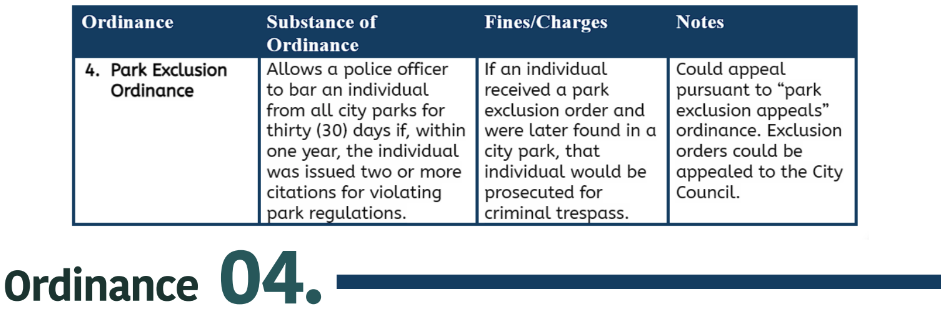

The ordinances at issue, in this case, are outlined below, which mirror harmful provisions STTARS has consistently identified in briefs, webinars, policy priority documents, factsheets, and our National Workgroup Reports. Specifically:

Starting with the first ordinance, sleeping, these ordinances effectively made criminal something that is a mere part of existing, simply based on the location of the individual. Often, we think about how our unhoused relatives lack safety and security due to a lack of shelter. Still, we occasionally fail to consider their lack of agency regarding their basic human functions. Criminalizing this means there is an insinuation that a base level of material accumulation is required to function as a person. This strips unhoused relatives of dignity, and it further dehumanizes them.

Additionally, civil fines that can mature into criminal citations are highly problematic for numerous reasons, but mainly because the criminalization of homelessness (which is what this ordinance does) does nothing to address the housing crisis that is occurring in Tribal communities, both on and off-reservation. Criminalization only further heightens bars to finding safe housing and shelter, especially for AI/AN survivors of gender-based violence. Shelters and programs enact policies and application processes, most of which ban discriminatory practices based on federal law. Many of these policies reflect that convictions are a total bar to accessing safe housing and shelter. Indigenous survivors of gender-based violence have multiple systems interactions as a part of their personal stories, including with the criminal justice system. During our listening sessions, survivors in four urban settings stated that these convictions, which were sometimes almost a decade year old or related to their experience of domestic violence and sexual violence, effectively barred them from safe shelter and housing. Even without maturing into criminal charges/convictions, cash fines and the inability to pay cash fines create additional unnecessary barriers for the unhoused. The city of Grants Pass does not publish the amount “recuperated” from these fines. Still, we would imagine that individuals without access to housing or shelter would have an incredibly difficult time paying a fine that can mature into $160.00.

This second ordinance prohibits campsites in public parks and permits law enforcement to remove/destroy the campsite and all personal property therein. During our travels to various urban settings where AI/AN survivors of gender-based violence reside, STTARS has personally witnessed the removal of encampments and the destruction of unhoused relatives’ belongings. Many of these operate as acts of unnecessary cruelty. Furthermore, without a place to keep important documents or identification, survivors are often left without the ability to access existing shelters or public housing spaces.

This third ordinance also punishes the unhoused for simply being unhoused. This one is especially problematic for survivors who are fleeing domestic violence or other forms of gender-based violence, often in a vehicle. Keeping survivors out of public spaces under these circumstances is incredibly dangerous, particularly where there is nowhere else to go (as is the case in Grants Pass, OR, which lacks the necessary shelter and safe housing space to house its current unhoused relatives safely. Additionally, this fine is incredibly punitive: $295.00 is excessive, especially when the conduct the fine punishes essentially amounts to poverty. Even worse, if the unpaid fine increases to $537.60.

This last ordinance further restricts unhoused individuals from accessing public spaces—one of the few remaining places where unhoused individuals can simply exist. The fact that this ordinance likely increases criminal trespass charges for our unhoused relatives makes it even more pernicious. While exclusion orders could be appealed to the City Council, it is clear that the city of Grants Pass consistently looks to harm its unhoused community members. It is unclear how successful any appeal would be in the environment/ culture that Grants Pass has fostered. Grants Pass has referred to unhoused relatives as “vagrants,” and since 2013, their city leaders have viewed these relatives as “issues.” In 2013, the City Council convened a “Community Roundtable” to “identify solutions to current vagrancy problems.” Multiple participants discussed “driving repeat offenders out of town and leaving them there.” A city councilor clarified that the city’s goal should be “to make it uncomfortable enough for [homeless persons] in our city so they will want to move on down the road.” This was parroted by a statement from the founder of the Sober Living Center in a later news article. The roundtable increased enforcement of the ordinances at issue in the case. Between 2014 and 2018, the city issued 574 tickets under its anti-camping and anti-sleeping ordinances.

What has been critically important to this case is the incredible lack of shelter and public housing space for unhoused individuals (during the case, the parties disagreed on how many involuntary homeless individuals lived in the city). Between the Plaintiff and Defendant in the 9th Circuit case, there was zero dispute around a key fact: Grants Pass had far more unhoused relatives than available shelter beds.

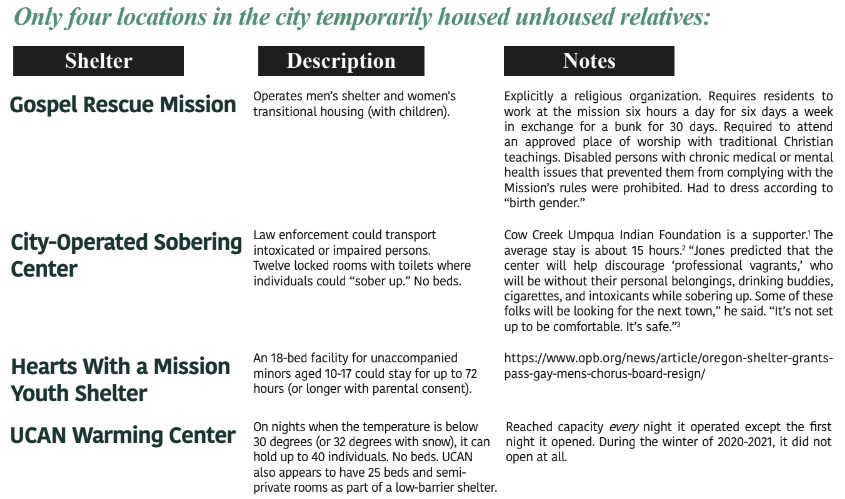

As STTARS has routinely stated in our resources (see next page) and policy spaces, there is a severe lack of housing, adequate housing, safe housing, shelter, etc., both on and off reservations where AI/AN and Native Hawaiians live. Grants Pass is no exception. At the time of the case, only four locations in the city temporarily housed unhoused relatives.

From a numbers standpoint, the available safe shelter and housing was inadequate. However, the form and function of the shelters were also highly problematic and increased barriers for unhoused relatives, including Indigenous survivors of gender-based violence.

Additionally, Foundry Village has since opened and is operated by Avista Connections. This village operates 17 tiny homes. Of the total funding, 80% comes from Medicare and Medicaid. The units have no running water or electricity (the common space has them.) Applicants must be 60 days clean and sober to access.4 Avista uses Rogue Retreat for case management and property management. A requirement of note—applicants must be drug and alcohol-free, including THC, which is legal in the state.

We know there is not enough housing or shelter to support the needs of AI/AN gender-based survivors in this region. Grants Pass, in particular, would need 4,000 units to support its unhoused community members. Community members of housed individuals in Grants Pass inhumanely distinguish themselves. In other words, some housed individuals in Grants Pass do not view unhoused relatives as members of their community simply by virtue of being unhoused.

Importantly, from our sessions, we know that AI/AN/NH survivors in the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon, cannot access the services they need. Furthermore, criminalization of unhoused relatives as a direct result of their being homeless is rampant. As we know from these listening sessions, this criminalization is almost a complete bar to securing safe housing.

In the first two years of its funding, STTARS has conducted numerous listening sessions with survivors, hosted 4 National Workgroup Meetings, and visited numerous programs and Tribes throughout the 50 states. Importantly, we have hosted listening sessions, site visits, and a workgroup meeting in the Pacific Northwest, where this case originated.

What is clear is the following: Grants Pass, as a community, tried to ensure the removal of its unhoused relatives specifically and expressly by making their lives unlivable.

1https://thesoberingcenter.org/

2https://bit.ly/3K6Ud8v

3https://auslandgroup.com/gp-sobering-center-preps-clients/

4https://bit.ly/3UM3VSx